A lot of people spend a lot of time trying to understand stock prices: Are they predictable? Are they random? Can you make money by identifying trends? Can you beat the market and make a fortune?

A prevailing theory is that stock prices are essentially random walks; that is, no more predictable than a coin flip. The amount a price goes up or down at any given moment might follow some pattern (small movement is more likely than large movement, for example), but whether that movement is up or down is basically random. Now, what random means to mathematicians can get kind of complicated, but that’s another story.

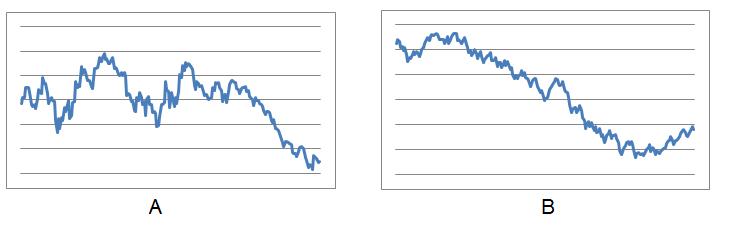

I thought it might be interesting to compare actual stock prices to a randomly-generated trend line. After playing around with a spreadsheet and experimenting with different parameters, I produced the following two graphs:

One of these graphs represents 200 days of prices of the Dow Jones Industrial average; the other represents a quantity that moves up or down randomly, by some random amount. Figuring out how to get a good-looking random graph took some time, and is an interesting challenge in and of itself.

So, can you tell which is the Dow and which is a coin toss? More importantly, how much would you be willing to bet on it?

Related Posts