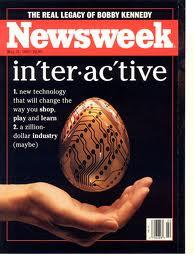

I really enjoyed reading Newsweek when I was younger–I loved the political cartoons, the quick-hit section in the front, the in-depth pieces on issues I knew nothing about. So I’ve been watching with interest as the Washington Post Company completes the sale of the news magazine for a reported $1 dollar and assumption of debt. Newsweek–like many print publications–has been losing money for a while, so this is not much of a surprise.

I really enjoyed reading Newsweek when I was younger–I loved the political cartoons, the quick-hit section in the front, the in-depth pieces on issues I knew nothing about. So I’ve been watching with interest as the Washington Post Company completes the sale of the news magazine for a reported $1 dollar and assumption of debt. Newsweek–like many print publications–has been losing money for a while, so this is not much of a surprise.

There are a lot of interesting stories going on here: the ongoing saga of print and online media; Sidney Harmon, of Harmon-Kardon audio fame, is the buyer and has no clear media experience; and Harmon’s wife, Jane, is a U.S. Representative. But it was the following analysis of the finances of Newsweek that really caught my interest:

http://www.cjr.org/the_audit/the_newsweek_numbers.php

Someone published a copy of the [presumably confidential] sales presentation on the web, and the revenue and cost data is fascinating: apparently Newsweek spent around $100 million (about 60% of its annual revenue of $160 million) to produce, distribute, and manage the physical magazine. How can a magazine, any magazine, seriously compete head-to-head with an online publication, one that can provide a similar service while avoiding $100 million in such costs?

This drastically changing industry is a good place to look at changing business and finance models.