My latest article for the New York Times Learning Network turns Steven Strogatz’s wonderful “Math, Revealed” essay on triangular numbers into a teaching and learning resource. Learn about how a favorite number pattern connects algebra, geometry, and calculus, and even extends into CAT scans the Fab Four!

The article is freely available here, and as with the articles in the series, include free access to Strogatz’s original New York Times essay.

Related Posts

- Unpack the Math of Packing, with Steven Strogatz and the New York Times

- Explore the Math Behind the Golden Ratio With Steven Strogatz and the New York Times

- Teach Taxicab Geometry with Steven Strogatz and the New York Times

- Investigating Gerrymandering and the Math Behind Partisan Maps

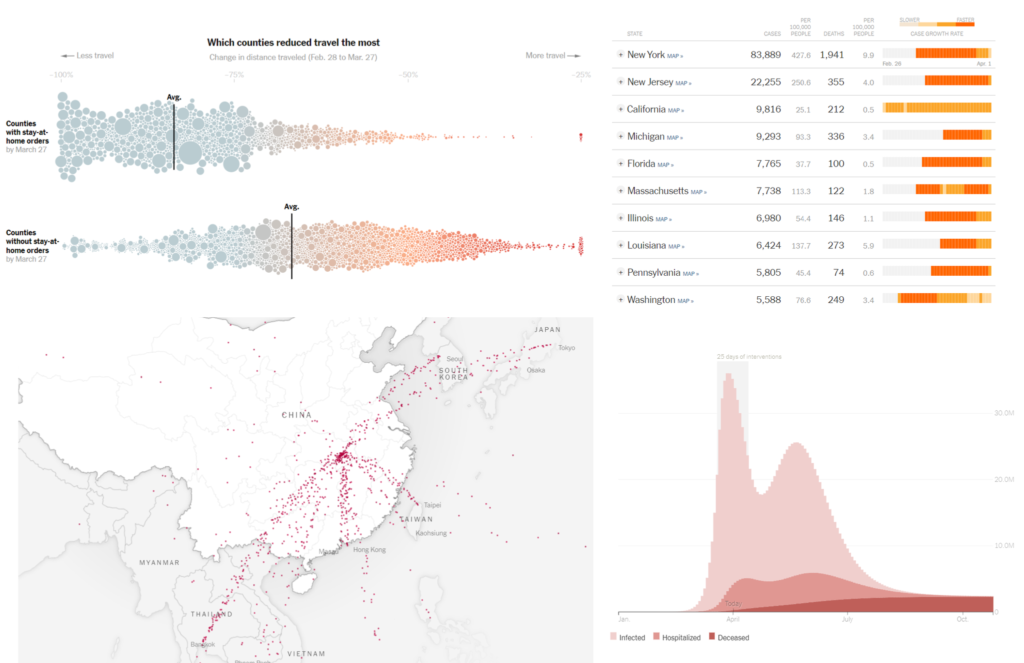

- Dangerous Numbers: Teaching About Data and Statistics Using the Coronavirus

- Moving on Up: Teaching with the Data of Economic Mobility

- N Ways to Apply Algebra with the New York Times

- NYT Learning Network