Well, Pi Day has already passed, but better late than never.

I spotted this on the wall of a college town’s pizza shop. I’ll give you 3.14 guesses which college.

Related Posts

Well, Pi Day has already passed, but better late than never.

I spotted this on the wall of a college town’s pizza shop. I’ll give you 3.14 guesses which college.

Related Posts

This week I will be co-facilitating a workshop for teachers, “Exploring Modern Discoveries in Mathematics and Science”, with Thomas Lin, editor-in-chief of Quanta Magazine. We will be running the workshop for a group of Math for America math and science teachers at the MfA offices.

This week I will be co-facilitating a workshop for teachers, “Exploring Modern Discoveries in Mathematics and Science”, with Thomas Lin, editor-in-chief of Quanta Magazine. We will be running the workshop for a group of Math for America math and science teachers at the MfA offices.

In our workshop we’ll look at ways to connect students and teachers with modern science research and discoveries. We’ll focus on resources from Quanta Magazine, including recent reporting on advances in mathematics, biology, and computer science, as well as some of my Quantized Academy columns.

I’m excited to be working with Tom, who in addition to being the founding editor of Quanta, is also a former teacher. Tom’s desire to make the amazing work being done by Quanta’s journalists and writers more accessible to teachers and students led to the development of my Quantized Academy column last year.

Be sure to check out Quanta Magazine, and you can find my Quantized Academy articles here.

Related Posts

Here is a fun little exploration involving a simple sum of trigonometric functions.

Consider f(x) = sin(x) + cos(x), graphed below.

Surprisingly, it appears as though sin(x) + cos(x) is itself a sine function. And while its period is the same as sin(x), its amplitude has changed and it’s been phase-shifted. Figuring out the exact amplitude and phase shift is fun, and it’s also part of a deeper phenomenon to explore.

Consider the function g(x) = a sin(x) + b cos(x). Playing around with the values of a and b is a great way to explore the situation.

On the way to a complete solution, a nice challenge is to find (and characterize) the values of a and b that make the amplitude of g(x) equal to one. It’s also fun to look for values of a and b that yield integer amplitudes: for example, 5sin(x) + 12cos(x) has amplitude 13, and 4sin(x) + 3cos(x) has amplitude 5.

Ultimately, this exploration leads to a really lovely application of angle sum formulas. Recall that

If we let A = x, we get

With a little rewriting, we have

which looks similar to our original function f(x) = sin(x) + cos(x), except for what’s in front of sin(x) and cos(x). We handle that with a clever choice of B.

Let . Now we have

And a little algebra gets us

And so sin(x) + cos(x) really is a sine function! Not only does this transformation explain the amplitude and phase shift of sin(x) + cos(x), it generalizes beautifully.

For example, consider 5sin(x) + 12cos(x). We can rewrite this in the following way.

where .

There’s quite a lot of trigonometric fun packed into this little sum. And there’s still more to do, like exploring different phase shifts and trying the cosine angle sum formula instead. Enjoy!

Related Posts

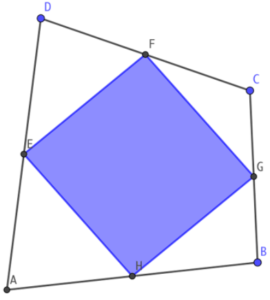

Following up on my appearance on the My Favorite Theorem podcast, co-host Kevin Knudson has an article in Forbes about Varignon’s Theorem, the topic of my episode. Kevin recaps some of the ideas we discussed, including my favorite proof of my favorite theorem.

Following up on my appearance on the My Favorite Theorem podcast, co-host Kevin Knudson has an article in Forbes about Varignon’s Theorem, the topic of my episode. Kevin recaps some of the ideas we discussed, including my favorite proof of my favorite theorem.

You can read the article here, and catch the full podcast episode on Kevin’s website.

Related Posts

Since the advent of the “Common Core” Regents exams in New York state, there has been a noticeable increase in decidedly Pre-Calculus content on the tests. Questions involving rates of change, piecewise functions, and relative extrema now routinely appear on the Algebra I and Algebra II exams. Unfortunately, these questions also routinely demonstrate a disturbing lack of content knowledge on the part of the exam creators.

Here’s number 36 from the January, 2018 Common Core Algebra I Regents exam.

This graph represents “the number of pairs of shoes sold each hour over a 14-hour time period” by an online shoe vendor. A simple enough start. But things start to get tricky halfway down the page, when the following directive is issued.

State the entire interval for which the number of shoes sold is increasing.

The answer must be 0 < t < 6, because that’s when the graph is increasing, right? The official rubric says so, and the Model Response Set backs it up (this Model Response has been edited to show only the portion currently under discussion).

But 0 < t < 6 is not the correct answer. Can you spot the wrinkle here? Basically, the number of shoes sold is always increasing.

The graph shown is a model of the number of shoes sold per hour. The model shows that, at any time between t = 0 and t = 14, a positive number of shoes are being sold per hour. In short, more shoes are always being sold. That means the number of shoes sold is always increasing. The correct answer is 0 < t < 14.

The exam creators have made a conceptual error familiar to any Calculus teacher: they are conflating a function and its rate of change.

In this problem, the directive pertains to the number of shoes sold. But the given graph shows the rate of change of the number of shoes sold. The given graph is indeed increasing for 0 < t < 6, but the question isn’t “When is the rate of change of shoes sold increasing?” The question is “When is the number of shoes sold increasing?” Since a function is increasing when its rate of change is positive, this means the number of shoes sold is increasing whenever the graph is positive. Thus, the answer is 0 < t < 14.

After the exam was given and graded, those in charge of the Regents exams became aware of the error. They quickly issued a correction, updated the rubric, and instructed schools to re-score the question (giving full credit for either 0 < t < 6 or 0 < t < 14). Thankfully, it didn’t take a change.org campaign and national media attention for them to admit their error.

But as usual, they did their best to dodge responsibility.

In their official correction, the exam creators blamed the issue on imprecision in wording, pretending that this was just a misunderstanding, rather than an embarrassing mathematical error. This is something they’ve done over and over and over again. These aren’t typos, miscommunications, or inconsistencies in notation. These are serious, avoidable mathematical errors that call into question the validity of the very process by which these exams are constructed, graded, and, ultimately, used. We all deserve better.

Related Posts