This is the first post in a dialogue between me and Grant Wiggins about rigor, testing, and the new Common Core standards. Each installment in this series will be cross-posted both here at MrHonner.com and at Grant’s website. We invite readers to join the conversation.

Patrick Honner Begins

After a spirited exchange on Twitter regarding New York State’s new Common Core-aligned tests, Grant Wiggins cordially invited me to continue our conversation about rigor in a collaborative blog post. It wasn’t until I saw his first suggested writing prompt—What is rigor?—that I suspected that perhaps I was being rope-a-doped by a master. But the opportunity was too intriguing to pass up.

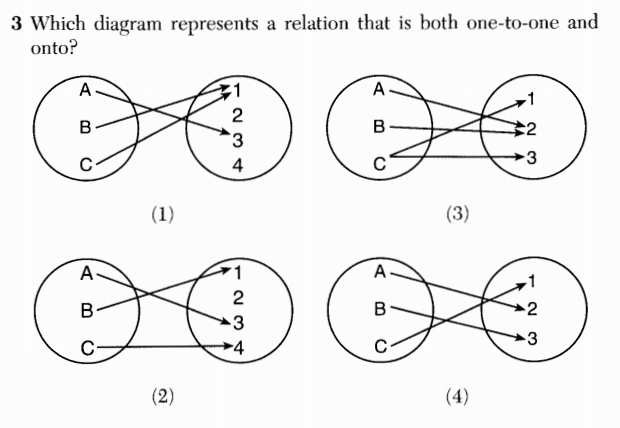

While I don’t expect to flesh out a fully-formed, operational definition of rigor, our conversation brought a couple of important ideas to mind regarding what it means for a mathematical test question or task to be rigorous.

Higher grade-level questions are not necessarily more rigorous

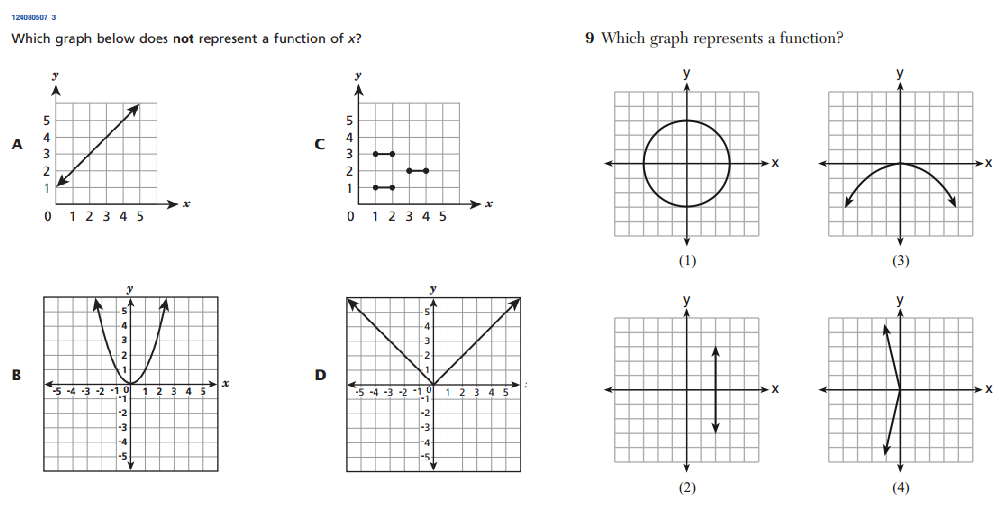

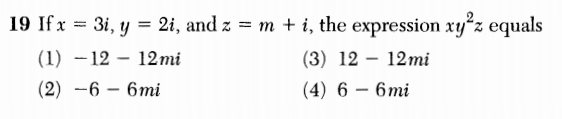

Our exchange began after I wrote a piece for Gotham Schools about the 8th grade Common Core-aligned test questions that were released by New York state. In reviewing the items, I noticed some striking similarities between these 8th grade “Common Core” questions and questions from recent high school math Regents exams.

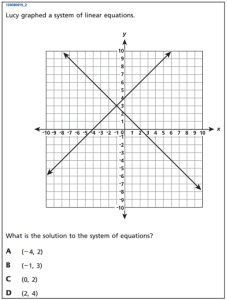

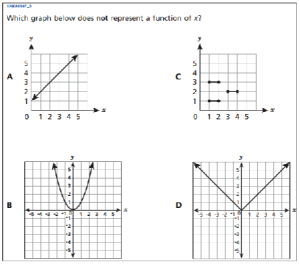

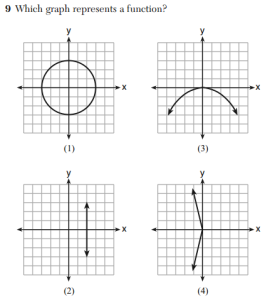

Above on the left we see a problem from the set of released 8th grade questions, and on the right, we see a virtually identical question that appeared on this January’s Integrated Algebra exam, an exam taken by high school students at all grade levels. (This was one of many examples of this duplication).

The annotations that accompany the released 8th grade questions suggest that this question requires that a student understand that “a function is a rule that assigns to each input (x) exactly one output (y)”. In reality, this question simply tests whether or not the student knows to apply the vertical line test to determine whether or not a given graph represents a function. If the student recalls this piece of content, the question is simple; if not, there is little they can be expected to do. It’s hard to imagine this particular question meeting anyone’s standard for rigor: it is a simple content-recall question. It is not designed to elicit any deep thinking or creative problem solving.

I was highly critical of the exam-makers for simply putting high school-level problem on the 8th grade exam and calling it more rigorous. In our Twitter exchange, Grant pointed out that a 10th grade question could be considered more rigorous, however, if the 8th grader had to reason the solution out rather than simply recall a piece of content. This excellent point led me to think about the subjective nature of rigor.

Rigor depends on the solution, and thus, the student

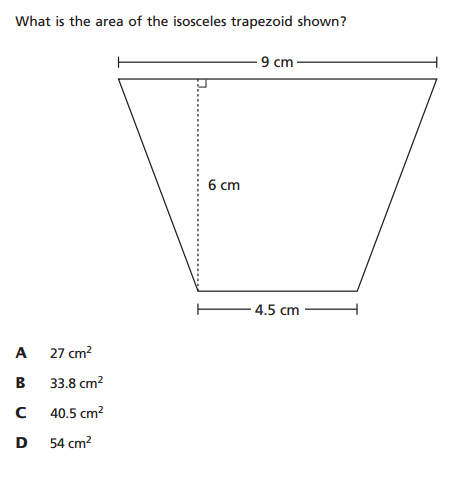

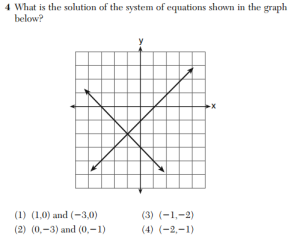

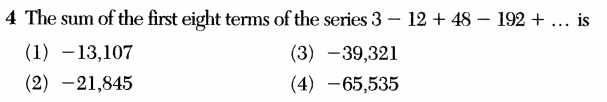

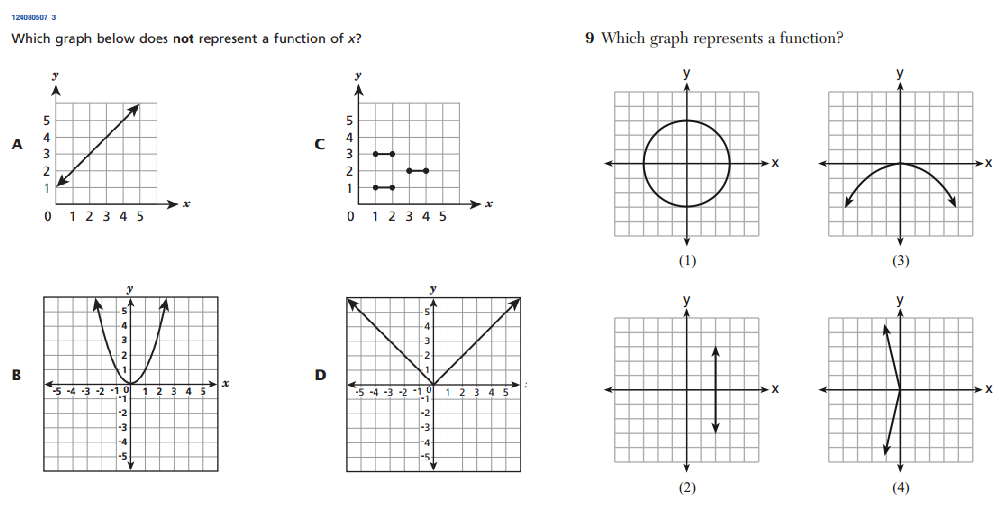

The following trapezoid problem from the 6th-grade exam is a good example of what Grant was talking about. It also illustrates the subjective nature of rigor.

Here, the student is asked to find the area of an isosceles trapezoid. According to the annotations, the student is expected to decompose the trapezoid into a rectangle and two triangles, use mathematical properties of these figures to determine their dimensions, find the areas, and then combine all of the information into a final answer. This definitely sounds like a rigorous task: the student is expected to think of a mathematical object in several ways, connect multiple ideas through several steps, and be precise in putting everything together.

The problem would be perceived much differently, however, if the student knew the standard formula for the area of a trapezoid (that is, area is equal to the product of the average of the bases and the height). Knowing that formula would make this a recall-and-apply-the-formula question, and not especially rigorous. Thus, this question might be considered rigorous in the context of 6th grade mathematics, but not in the context of 8th grade mathematics.

But if a 6th grade student happens to know the formula for the area of a trapezoid, they’ll get the answer faster while sidestepping all the messy details; that is, the rigor. And it won’t take long for students and teachers to realize that memorizing higher-level formulas might help them navigate these rigorous exams more efficiently and effectively. These rigorous questions, whose rigor depends in part on a lack of advanced content knowledge, might actually encourage some decidedly un-rigorous behavior in students and teachers.

Grant Wiggins Responds

I agree with your first two points. Just because a question comes from a higher grade level doesn’t make it rigorous. And rigor is surely not an absolute but relative criterion, referring to the intersection of the learner’s prior learning and the demands of the question. (This will make mass testing very difficult, of course).

To me, rigor has (at least) 3 other aspects when testing: learners must face a novel(-seeming) question, do something with an atypically high degree of precision and skill, and both invent and double-check the approach and result, be it in math or writing a paper. The novel (or novel-seeming) aspect to the challenge typically means that there is some new context, look and feel, changed constraint, or other superficial oddness than what happened in prior instruction and testing. (i.e. what Bloom said had to be true of any “application” task in the Taxonomy).

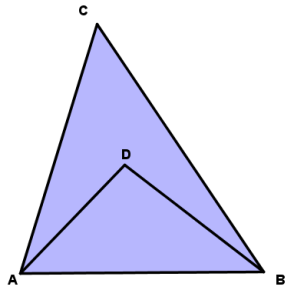

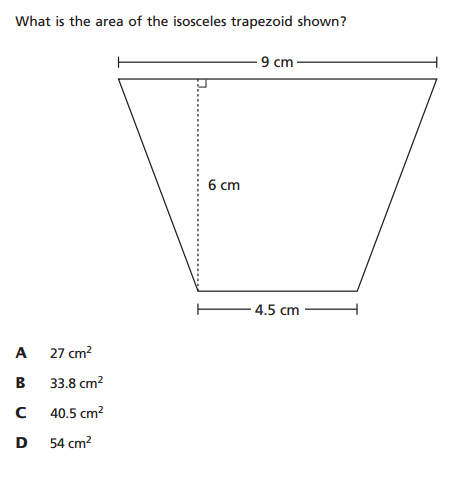

I would go further: depending upon context, a problem can go from hard to easy and easy to hard. Case in point – a great example from Michalewicz and Fogel’s book on heuristics:

“There is a triangle ABC, and D is an arbitrary interior point of this triangle. Prove that AD + DB < AC + CB. The problem is so easy it seems as if there is nothing to prove. It’s so obvious that the sum of the two segments inside the triangle must be shorter than the sum of its two sides. But this problem is now removed from the context of its chapter, and outside of this context the student has no idea of whether to apply the Pythagorean Theorem, build a quadratic equation, or do something else!

“The issue is more serious than it first appears. We have given this very problem to many people, including undergraduate and graduate students, and even full professors of mathematics, engineering and computer science. Fewer than 5% of them solved this problem within an hour, many of them required several hours, and we witnessed some failure as well.” (pp. 4-5)

It is helpful here to bring in Paul Zeitz and his clear account of the difference between an exercise and a (real) problem to flesh out my claim that rigor requires the latter, not the former (which is your point, too): “An exercise is a question that you know how to resolve immediately. Whether you get it right or not depends upon how expertly you apply specific techniques, but you don’t need to puzzle out what techniques to use. In contrast, a problem demands much thought and resourcefulness before the right approach is found.”

The first two authors go on to say that real problems are very difficult to solve, for several reasons:

- The number of possible solutions in the search space is so large as to forbid an exhaustive search for the best answer.

- The problem is so complicated…we need to use simplified models

- The evaluation function is ‘noisy’ or varies in time.

- The possible solutions are so heavily constrained that constructing even 1 feasible answer is difficult.

- The person solving the problem is inadequately prepared or imagines some psychological barrier that prevents them from discovering a solution.

To me the 2nd and 4th elements are key.

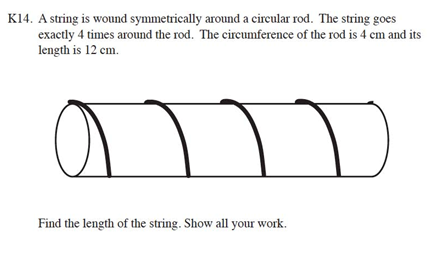

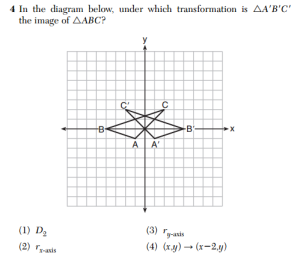

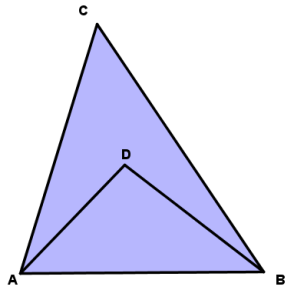

Here is one of my favorite such problems, from the TIMSS over a decade ago:

Here’s what a NY Times Reporter wrote about this problem:

Here’s what a NY Times Reporter wrote about this problem:

“The problem is simply stated and simply illustrated. It also cannot be dismissed as being so theoretical or abstract as to be irrelevant for the technocrats of tomorrow. It might be asked about the lengths of tungsten coiled into filaments; it might come in handy in designing computer chips where distances are crucial. It seems to involve some intuition about the physical world and some challenge about how to determine something about that world.

It also turned out to be one of the hardest questions on the test. The international average of advanced mathematics students [in 12th grade] who got at least part of the question correct was only 12 percent (10 percent solved it completely). But the average for the United States was even worse: just 4 percent for a complete solution (there were no significant partial solutions).”

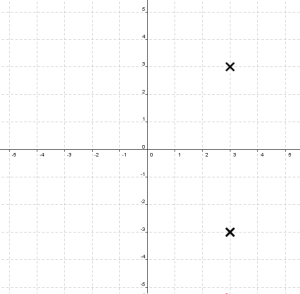

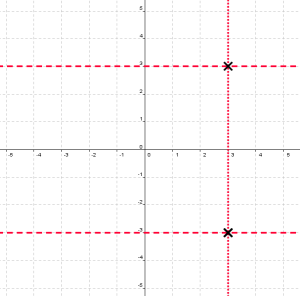

By EDWARD ROTHSTEIN (NYT); Business/Financial Desk, March 9, 1998, Monday

So, the challenge in math teaching – always! – is to come up with real problems, puzzling challenges that demand thought, not just recall of algorithms (mindful of the fact that in mass testing some kids will get lucky and have instant recall of such a problem and its solution).

My favorite sources? The Car Talk Puzzlers, and Math Competition books. But there is more to be said on the subject of ‘novel’ problems via mass testing.

Read Part 2 of the conversation here.