Having put some thought into the mathematics of the NFL draft, I decided to turn my attention to basketball. From an anecdotal perspective, the NBA draft seems to be more hit-or-miss than the NFL draft: teams occasionally have success and draft a great player, but it seems more common that a draft pick doesn’t achieve success in the league.

Having put some thought into the mathematics of the NFL draft, I decided to turn my attention to basketball. From an anecdotal perspective, the NBA draft seems to be more hit-or-miss than the NFL draft: teams occasionally have success and draft a great player, but it seems more common that a draft pick doesn’t achieve success in the league.

In an attempt to quantify the “success” of an NBA draft pick, I researched some data and ending with choosing a very simple data point: the total minutes played by the draft pick in their first two seasons.

Total minutes played seems like a reasonable measure of the value a player provides a team: if a player is on the floor, then that player is providing value, and the more time on the floor, the more value. I looked only at the first two seasons because rookie contracts are guaranteed for two years; after that, the player could be cut although most are re-signed. In any event, it creates a standard window in which to compare.

There are plenty of shortcomings of this analysis, but I tried to strike a balance between simplicity and relevance with these choices.

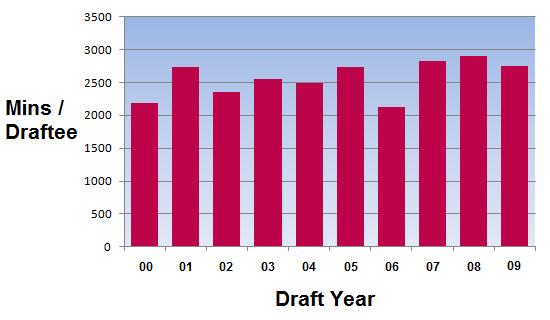

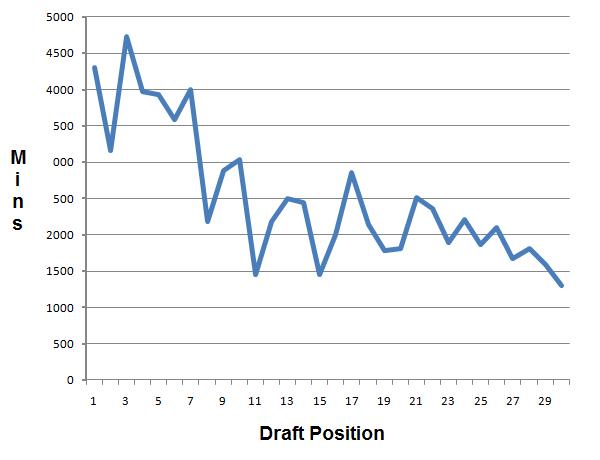

I looked at data from the first round of the NBA draft between 2000 and 2009. For each pick, I computed their total minutes played in their first two years. I then found the average total minutes played per pick over those ten drafts.

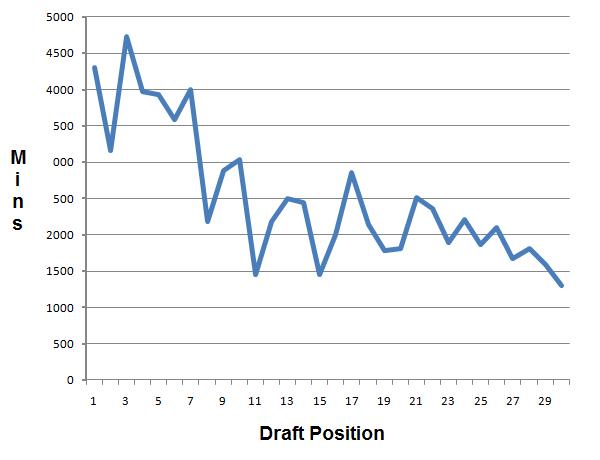

Not surprisingly, the average total minutes played generally drops as the draft position increases. If better players are drafted earlier, then they’ll probably play more. In addition, weaker teams tend to draft higher, and weak teams likely have lots of minutes to give to new players. A stronger team picks later in the draft, in theory drafts a weaker player, and probably has fewer minutes to offer that player.

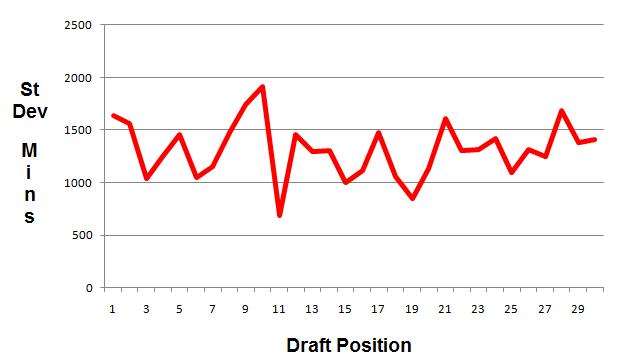

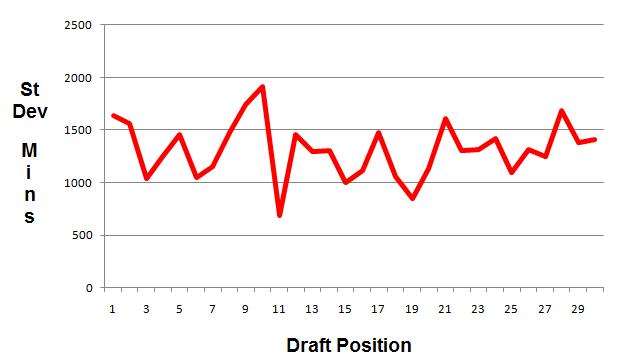

However, when I looked at the standard deviation of the above data, I found something more interesting. Standard deviation is a measure of dispersion of data: the higher the deviation, the farther data is from the mean.

Notice that the deviation, although jagged, seems to bounce around a horizontal line. In short, the deviation doesn’t decrease as the average (above in blue) decreases.

If the total number of minutes played decreases with draft position, we would expect the data to tighten up a bit around that number. The fact that it isn’t tightening up suggests that there are lots of lower picks who play big minutes for their teams. This might be an indication that value in the draft, rather than heavily weighted at the top, is distributed more evenly than one might think

This rudimentary analysis has its shortcomings, to be sure, but it does suggest some interesting questions for further investigation.

Related Posts

Through Math for America, I am part of an on-going collaboration with the New York Times Learning Network. My latest contribution, a Test Yourself quiz-question, can be found here:

Through Math for America, I am part of an on-going collaboration with the New York Times Learning Network. My latest contribution, a Test Yourself quiz-question, can be found here: