This is the second entry in a series that examines the test quality of the New York State Math Regents Exams. In the on-going debate about using student test scores to evaluate teachers (and schools, and the students themselves), the issue of test quality rarely comes up. And the issue is crucial: if the tests are ill-conceived, poorly constructed, and erroneous, how legitimate can they be as measures of teaching and learning?

In Part 1 of this series I looked at three questions that demonstrated a significant lack of mathematical understanding on the part of the exam writers. Here, in Part 2, I will look at three examples of poorly designed questions.

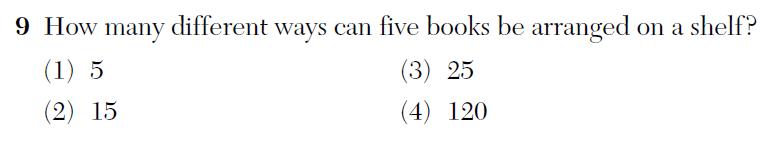

The first is from the 2011 Integrated Algebra Regents: how many different ways can five books be arranged on a shelf?

This simple question looks innocent enough, and I imagine most students would get it “right”. Unfortunately, they’ll get it “right,” not by answering the question that’s been posed, but by answering the question the exam writers meant to ask.

How many different ways are there to arrange five books on a shelf? A lot. You can stack them vertically, horizontally, diagonally. You can put them in different orders; you can have the spines facing out, or in. You could stand them up like little tents. You could arrange each book in a different way. The correct answer to this question is probably “as many ways as you could possibly imagine”. In fact, exploring this question in an open-ended, creative way might actually be fun, and mathematically compelling to boot.

But students are trained to turn off their creativity and give the answer that the tester wants to hear. A skilled test-taker sees “How many ways can five books be arranged on a shelf?” and translates it into “If I ignore everything I know about books and bookshelves, stand all the books upright in the normal way, don’t rotate, turn or otherwise deviate from how books in math problems are supposed to behave, then how many ways can I arrange them?”

This question is only partly assessing the student’s ability to identify and count permutations. This question mostly tests whether the student understands what “normal” math problems are supposed to look like.

This problem is an ineffective assessment tool, but there’s something even worse about it. Problems like this, of which there are many, teach students a terrible lesson: thinking creatively will get you into trouble. This is not something we want to be teaching.

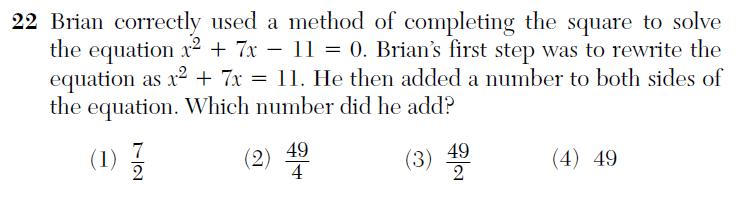

Here’s a question from the 2011 Algebra II and Trigonometry exam:

Solving equations is one of the most important skills in math, and this question pertains to a particular method (completing the square) used to solve a particular kind of equation (quadratic). But instead of simply asking the student to solve the problem using this method, the question asks something like “if this procedure is executed normally, what number will be written down in step four?”.

This is not testing the student’s ability to do math; instead, it’s testing whether or not they understand what “normal” math looks like. There are many ways to solve equations, and there are many ways a student might use this method. Whether it looks exactly like what the teacher did, or what the book did, isn’t especially relevant. So why is that being tested? And like the question above, this reinforces the idea that thinking creatively can be dangerous by insisting that students see the “normal” solution as the only correct one.

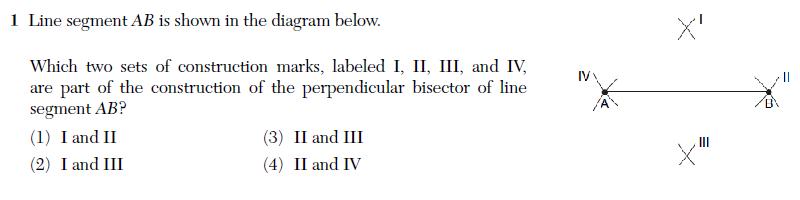

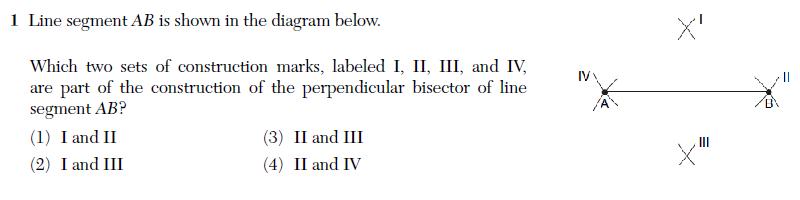

Finally, here’s a problem from the 2011 Geometry Regents:

Once again, the student is not being tested on their knowledge of a concept or on their ability to perform a task. Instead, they’re being tested on whether or not they recognize what “normal” math looks like, and that’s just not something worth testing. There are lots of legitimate ways to construct a perpendicular bisector: why are we testing whether the student recognizes if the “normal” way has been used?

These three problems showcase some of the dangers inherent in standardized testing. Questions like these, and the tests built from them, discourage creative thinking; they send students the message that there is only one right way to do things; they reinforce the idea that the “correct” answer is whatever the tester, or teacher, wants to hear; and they de-emphasize real skills and understanding.

At their worst, these tests may not just be poor measures of real learning and teaching; they may actually be an obstacle to real learning and teaching.

Related Posts