2019 was another good reading year for me. I mostly kept pace with previous years and read many great books. Here are some that stuck with me.

It was a good year for calculus books. Steven Strogatz’s Infinite Powers is a great read for any math enthusiast, and a must read for math teachers. It tells the story of calculus in a fun and engaging way, making the mathematics meaningful while putting it in historical context. It had an immediate impact on how I taught calculus last year, and I’ve been going back to it this year to share characters, anecdotes, and beautiful math.

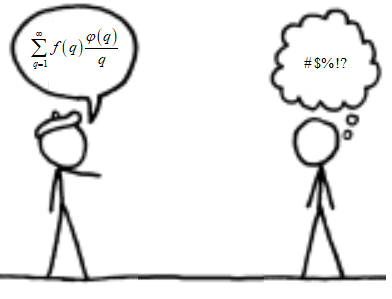

Ben Orlin’s Change is the Only Constant is a different, but equally compelling, kind of calculus book. I think I best described it in this tweet: “@benorlin‘s book is simultaneously high brow and goofy, deep and easy going, important and self-deprecating, but always fun and enlightening. In other words, it’s uniquely Ben Orlin.” Apparently the working title for the book was “Calculus for Poets“, which definitely makes sense.

I read several other good books in the math and science space. Hannah Fry’s Hello World is full of stories that put the age of algorithms in context: It’s a nice complement to Cathy O’Neil’s Weapons of Math Destruction, offering a more hopeful and optimistic take on some of the same issues. And for some reason I ended up reading several books on physics this year, with Sabine Hossenfelder’s Lost in Math the most memorable. Hossenfelder tries to make sense of the pervasive role of beauty in theorizing about physics, interviewing leading thinkers while interrogating her own ideas. I appreciated her skepticism and her frustration, and her book reminded me of my philosophy of science professor, who once told me “Scientists like to think of themselves as philosophers, but they don’t do a very good job at it.”

John Urschel’s Mind and Matter, written with Luisa Thomas, is a math memoir of sorts. It’s a quick and compelling read about a man driven by his parallel passions for mathematics and football. After reaching the NFL and playing for the Baltimore Ravens, Urschel retired after three seasons to purse his PhD at MIT full-time. It’s a fun and fascinating story, and one you can tell is just beginning.

Make it Stick, by Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel, was one of the most impactful books I read this year. Filled with stories and examples of “The Science of Successful Learning”, it has greatly influenced the way I think about and talk about my approach to teaching. Every teacher should know about the testing effect, spaced retrieval, and the science of forgetting.

I continued to read a lot of science fiction in 2019. I really enjoyed the Broken Earth Trilogy by N.K. Jemisin, a post-apocalyptic fantasy set on a world seemingly determined to rid itself of its inhabitants. And months later I’m still thinking about The Doomsday Book, by Connie Willis, which read more like a detailed first-person history of the bubonic plague era than a time-travel story.

I also continued to find some comfort in history. Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power, by Jon Meacham, tells of Jefferson’s many successes and failures against the backdrop of the establishment of America. The book does not lionize Jefferson, nor the era, and it certainly helps put the current state of our world in clearer context.

In non-fiction, Tara Westover’s Educated was hard to put down. It’s a powerful story about a remarkable young woman’s escape from the grip of a survivalist family that is at once both hard to believe and yet somehow all too real. I also enjoyed John McPhee’s Oranges, which is about, well, oranges.

I re-read The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckeberry Finn this year, which were as fun and irreverent and insightful as I remember. And Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart was undoubtedly the most beautiful book I read this year. It’s a moving story about pride and loss, power and powerlessness, and what change leaves behind.

Many of my favorite books this year came from recommendations, so thank you for reading great books and telling me about them! And as always, my thanks to the Brooklyn Public Library and the New York Public Library system for making this all so easy.

Related Posts