My heart sank a little as I watched the video.

It had been three months since I submitted my application for the Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching (PAEMST). As I often do in the summer, I was reviewing materials from the school year, cleaning up and getting organized. I found my PAEMST application folder, noticed the video — the centerpiece of the application portfolio — and clicked play.

I remembered feeling pretty good about the lesson I chose to record. Re-watching it months later confirmed that it was a good lesson. But it wasn’t flashy. I didn’t perform a rap about even and odd functions. Students weren’t chasing each other around the classroom in a relay race. I didn’t dramatically slice a melon in half with a meat cleaver. My chance of earning the country’s highest honor for K-12 STEM teachers hinged on this video, but it was just me teaching a normal lesson. I resigned myself to the fact that my odds probably weren’t very good.

But as I continued to watch the video, my attitude slowly changed. No, it wasn’t flashy — my lessons never are — but it was a really good lesson. It was well-designed, well-executed, and well-received. Students were deeply engaged in complex mathematics. There was a clear arc that everyone could connect with. By the end of the video, my resignation had turned to pride: This is what happens every day in our classroom. This is who I am as a teacher. This was a normal day: exactly the right way to represent myself and my work.

I know what kind of teaching captures the public’s interest, and this wasn’t it. But I was proud of what was showcased in the video, even if it might not look like “great teaching” to an outside observer. Would PAEMST reviewers appreciate the well-chosen problems that bridged prior knowledge and new concepts? Would they notice the classroom culture in which students immediately began collaborating, seeking each other’s validation before mine? Would they see the subtle changes I made after assessing small group discussions? Would they appreciate how I strategically answered some questions and respectfully put others right back to the students? Would they notice how students listened to each other during whole-class discussion? How they comfortably responded to each other’s questions? How they made conjectures that would be resolved later in the lesson?

I guess they did.

I received the Presidential Award in 2013. Here I am, between then-US CTO Megan Smith and Dr. France Cordova, Director of the National Science Foundation. It was a tremendous honor to win the PAEMST and to travel to Washington D.C. to meet leaders from the National Science Foundation, the National Academy of Sciences, and the White House. And meeting and connecting with other awardees — teachers doing great work in all manners of classrooms, schools, and communities across the country — continues to impact the work I do.

And it was encouraging to know that those responsible for awarding the PAEMST understood what they were looking at when they watched my video: nothing flashy, just good teaching. The kind that happens in my classroom, and countless others around the country, every day. Years later, I still occasionally look at my PAEMST application materials: the essays, the artifacts, even the video. It’s a nice snapshot of where I was at in 2013, and it’s fun and productive to think about the ways I’ve changed, and stayed the same, as a teacher.

Creating that snapshot is one of the many reasons I encourage teachers to apply for the PAEMST. The application process is a worthwhile professional experience in and of itself. It’s the kind of work good teachers want to do anyway: planning instruction; thinking about curriculum; analyzing outcomes; reflecting on process. Applying for the Presidential Award is a great motivator to do that work.

Teachers out there who feel ready should consider applying. And if you know a great teacher, you can nominate them for the Presidential Award. The process alone is worth it, and the potential reward is career-changing.

Related Posts

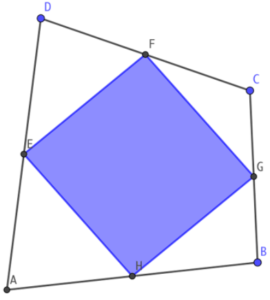

Following up on my appearance on the My Favorite Theorem podcast, co-host Kevin Knudson has an article in Forbes about Varignon’s Theorem, the topic of my episode. Kevin recaps some of the ideas we discussed, including my favorite proof of my favorite theorem.

Following up on my appearance on the My Favorite Theorem podcast, co-host Kevin Knudson has an article in Forbes about Varignon’s Theorem, the topic of my episode. Kevin recaps some of the ideas we discussed, including my favorite proof of my favorite theorem.